India's flagship fifth-generation fighter jet program, the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA), faces significant headwinds as private industry has shown no interest in becoming a full development partner.

The Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA), a division of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), has once again extended the deadline for bid submissions to September 30, 2025, after receiving zero proposals from private sector consortiums for the aircraft's critical engineering and development phase.

The lack of private participation highlights a major challenge for the nation's 'Atmanirbhar Bharat' (Self-Reliant India) initiative in the defence sector.

The AMCA program is strategically vital for the Indian Air Force (IAF), which is currently operating with approximately 31 fighter squadrons against a sanctioned strength of 42.5 needed to manage a two-front threat scenario.

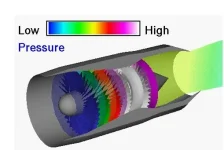

Designed as a 25-tonne, twin-engine stealth aircraft, the AMCA is intended to be India’s answer to advanced fighters in the region, including China’s Chengdu J-20 and Pakistan's future J-35A fleet.

The government's plan, approved by the Cabinet Committee on Security in March 2024, involves an initial allocation of ₹15,000 crore for the Full-Scale Engineering Development (FSED) phase. This phase covers the design, development, and testing of five prototypes, with a projected first flight by 2028-29.

The total program is estimated to cost ₹1.2 lakh crore for the production of 120 to 150 aircraft, which will eventually replace the IAF's ageing Mirage 2000 and Jaguar fighter fleets.

However, the private sector has remained on the sidelines, expressing deep reservations about the financial and technical terms of the partnership.

At the heart of the industry's reluctance are concerns over profitability and risk. While the Expression of Interest (EoI) invites private companies to become full equity partners, executives find the business case unconvincing. They point to the modest initial FSED funding and the lack of clear assurances on profit margins and risk-sharing.

Many leading defence firms, including Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL), Larsen & Toubro (L&T), and Bharat Forge, prefer the security of their current roles as tier-suppliers. In these positions, they manufacture components for projects like the Rafale, Tejas, and C-295 transport aircraft, which provides a steady revenue stream with significantly lower financial exposure.

Furthermore, the technical complexity and rigid contractual terms of the AMCA project present formidable barriers. The program involves mastering cutting-edge technologies such as advanced stealth materials, AI-driven sensor fusion, and the co-development of a new 110-kilonewton engine. The EoI requires bidders to establish dedicated production facilities and take on full design responsibility within a strict eight-year timeline.

Industry insiders have noted that these conditions disproportionately favour the state-owned Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), which has existing infrastructure and a long history with the defence establishment.

The legacy of the 30-year-long development cycle of the Tejas Light Combat Aircraft has also made private firms cautious about committing capital to another large-scale indigenous program prone to bureaucratic delays.

Despite the government’s efforts to attract private investment, including amendments to the EoI and promises of easier access to IAF testing facilities, the core issues remain unaddressed.

Defence Secretary Rajesh Kumar Singh stated in July 2025 that the government was prepared to "ease entry barriers," but this has not been sufficient to generate a bid.

Private companies argue that without fundamental changes to the commercial terms, such as guaranteed returns, clear intellectual property rights, and a more balanced risk-sharing model, they cannot justify the massive upfront investment required to become a full partner.

The continued absence of bids places the ambitious timeline for the AMCA in jeopardy. While HAL is reportedly in discussions to form its own consortium, the government's goal of fostering a competitive and robust private defence manufacturing ecosystem through this project is yet to materialise.

The success of India’s most critical aviation program now appears to depend on whether the Ministry of Defence can formulate a more attractive and commercially viable proposal that aligns risk with reward for the private sector.